By Diego Borja Cornejo*

The Greek Prime Minister, Alexis Tsipras, has called a referendum so that it will be up to the Greek people to decide if the austerity demanded by the Eurogroup is to continue.

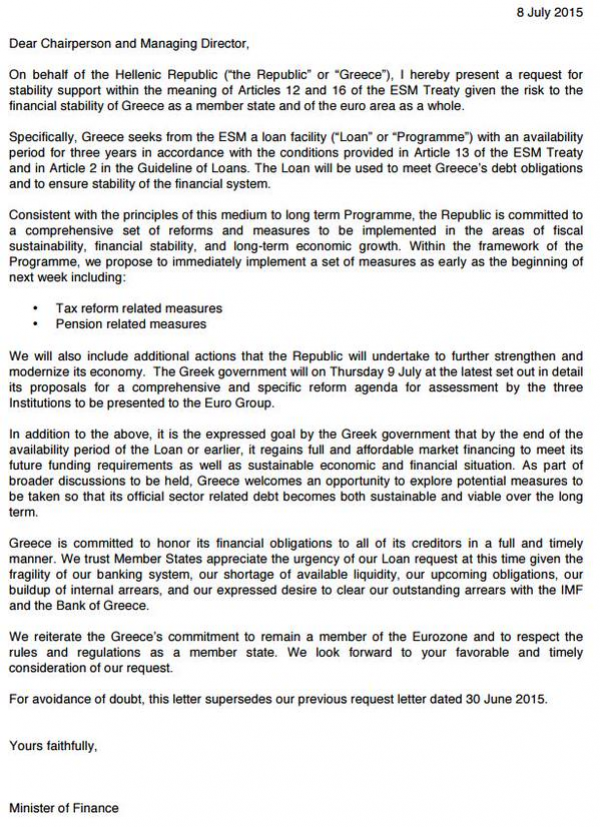

Tsipras took this decision after several months of negotiating with a European Union, a European Central Bank and an International Monetary Fund which have, in recent months, rejected time and time again the Greek proposal to reach a compromise that is acceptable to a government that won the elections on a platform to limit austerity.

The Greek parliament has approved the call for a referendum and given the Prime Minister its backing and now Tsipras has turned to the Greek people so that they can decide if continuing austerity, which has been a noose strangling both the population’s welfare and economic growth, is an option they can accept.

The leaders of “democratic” Europe wasted no time in furiously criticising his decision. In a blatant contradiction, across Europe the governing establishment, whether conservative, liberal and “socialist”, spoke in the name of “democracy and responsibility” and launched an attack on Tsipras’s essentially democratic action of appealing to the people.

Europe’s democracy is being played out in Greece. The top bureaucrats at the institutions, with a stubbornness that can only come from clearly seeing themselves as guardians of power and financial capital, are not budging one inch in their demands regarding the tried-and-tested austerity, which has been a social and economic disaster for Greece. As stated in the Preliminary Report by the Greek Debt Truth Committee, set up by the speaker of the Greek parliament, Zoe Konstantopoulou, the austerity policies have had a dramatic impact on investment. Gross capital formation fell by 65% in 2014 compared with 2008 and labour productivity by 7%. The capital capacity utilisation rate dropped from 75.5% in the period between 2006 and 2010 to 67.7% in 2014. Continue reading